Where do I belong? For me this is a fraught question, as it is for many migrants.

When the migrant ship Australis slowly manoeuvred out of Cape Town’s docks in December 1974 and set off for the open sea I stood on the deck and watched as the majestic Table Mountain, under the shadow of which I had been born, receded into the distance. I felt an enormous sense of relief and I vowed never to return. Then the mountain disappeared over the horizon and I felt as if I had escaped from a prison. I couldn’t stand the place, with its racist, authoritarian government and its ultra-conservative, pious Afrikaners, who had as much compassion for people of colour as a predator has for its prey.

I have now lived in Australia for more than sixty percent of my entire life, so this is clearly where I belong, right? The places of my youth have changed beyond recognition, so surely I now no longer belong there. And yet, I am not always sure where I really belong. The place where one has lived as a child and as a young person is indelibly engraved into one’s psyche, regardless of the passage of time. Its tendrils retain a firm hold over the years. And so it is with me.

What is it that binds us forever to the places of our youth? It is the landscapes, the shape of the trees, the native flowers and birds and animals, the smells. It is the accents and the unique local sense of humour of the people. Even after forty years away my heart still soars when I hear Cape Coloured people speak their distinctive Kaapse Afrikaans, or when I hear the clicking sounds of a black person speaking Xhosa or Zulu.

A few years ago I borrowed my brother’s car and drove along the road between Gordon’s Bay and Hangklip, near my home town of Somerset West. The road winds its way between the ocean on one side and steep mountains on the other. As a young man I went there nearly every weekend, having barbecues with friends or girlfriends, snorkelling and sunbaking.

I spotted some wild proteas on the slope of the mountain, near the road. When I stopped and walked up the slope I suddenly smelled the aroma of the fynbos, the local vegetation, and was overpowered by the familiarity of the smells. I can’t even remember having ever registered these smells when I was young. I was so excited that I kept sniffing at the plants. Then I realised if anyone spotted me they would probably think I had escaped from a mental institution.

During the forty plus years that I have lived in Australia I have naturally grown to love the smell and the shape of the gum trees and I adore the sounds of the warbling magpies and currawongs. They have also become a part of my psyche.

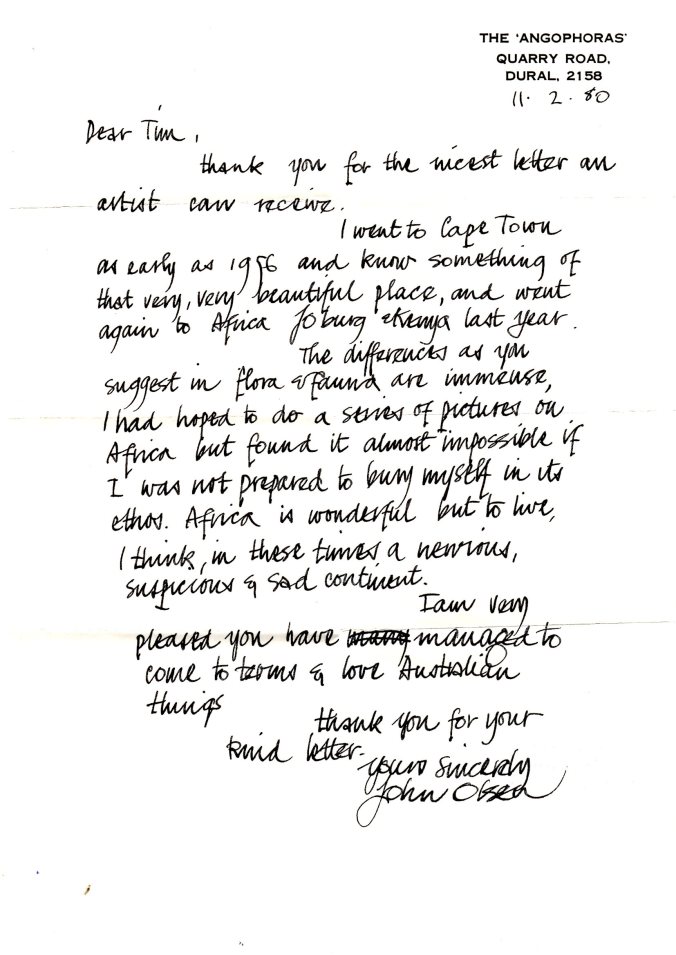

When I was working at the Glen Waverley Library five years after I had arrived in Australia, I came across a book called Wild Australia: a view of birds and men, with paintings and drawings by the Australian artist John Olsen. His illustrations struck a strong chord within me and I realised for the first time the extent to which Australia had become “my place”.

At the time I was a complete ignoramus as far as art was concerned and I had never heard of Olsen. I wrote to him that same day and explained how I had struggled to come to terms with Australia’s animal and plant life and landscapes, which differed so much from that which I had grown up with. I told him his art work had captured the essence of Australia’s places and it had made me realise that I really felt at home in my new country.

Olsen responded:

Ironically, when I am traveling in South Africa these days and I see a eucalypt or a callistemon with its red bottlebrush flowers, I immediately long for “home”. Such is the ambivalence of my belonging.

A couple of years ago I caught up with Johan, a university friend, in South Africa. It was the first time I had seen him since I had left my homeland all those decades ago. We had lost touch with each other when I departed, but now we were overjoyed to meet again.

“It’s so good to see you again after all these years, Tiens. I had heard somewhere that you had gone to Australia and I’ve often wondered how you were going there and what you were doing.” Then he added, “So when are you coming home?”

And for a little while there I felt I was ‘home’.

The writer Gillian Slovo, daughter of a South African political refugee, described this ambivalence perfectly in an article in The Bookseller of 31 January 1997:

North London is where I’ve lived most of my life. But there are things about South Africa that feel more like home to me … I have to deal with the fact that, like most exiles, I am at home in two places, and a stranger in both.

My children do not suffer from the same ambivalence as their father. When my son Neil was six years old I took him and a couple of his little mates to the local swimming pool one day. They were all sitting in the back of the car. I overheard one friend asking Neil, “Why does your dad speak so funny?”

“How do you mean?’ asked Neil.

“He doesn’t speak the same as us Aussies.”

“Oh,” Neil replied. “That’s because me dad’s an Afro. And me mum’s a Pom, but me – I’m an Aussie!”

Well done Tim the last sentence says it all

stay happy, take care, John D[http://gfx2.hotmail.com/mail/w3/ltr/emoticons/smile_regular.gif]

________________________________

LikeLike

Glad you came to Aus Tim, think what we would have missed if you didn’t.

LikeLike

Many thanks for that Al.

LikeLike

I too have been in Australia for over 60% of my life Tim, and I fully understand your sentiments. But the difference is that I don’t find I’ve a great yearning for the country of my birth, many good memories yes, but no ties. I think I became an Aussie around 1980 and it still irks me that many people still think I barrak for the English cricket team.

LikeLike

They do need your support at the moment Nick!

LikeLike

Hi Timmy,

Nice snapshot of your conversion to our wonderful country and your reconciliation of reuniting with your homeland. Good onya cobber, you’ll do me for a dinky die ozzie!

LikeLike

Onya mate! Thanks for that.

LikeLike